“Right to Shelter” No Longer Exists for Thousands of Migrants in New York

After 42 years, New York City’s “right to shelter,” which was intended to ensure immediate access to a bed for anyone in need, has effectively come to an end.

Mayor Eric Adams has been issuing warnings for months about the impending arrival of this moment, going as far as taking the city to court earlier this spring in an attempt to be released from the consent decree it had entered into decades ago.

The right to shelter for adult migrants was not revoked through a public announcement or a court ruling. Rather, it was silently taken away.

The Adams administration has brought an end to the era of opening shelters in improvised settings to accommodate the increasing number of migrants arriving in New York. City workers had been working tirelessly for months to create more shelters, but now the approach has changed. The administration has decided to let the chips, and the people, fall where they may.

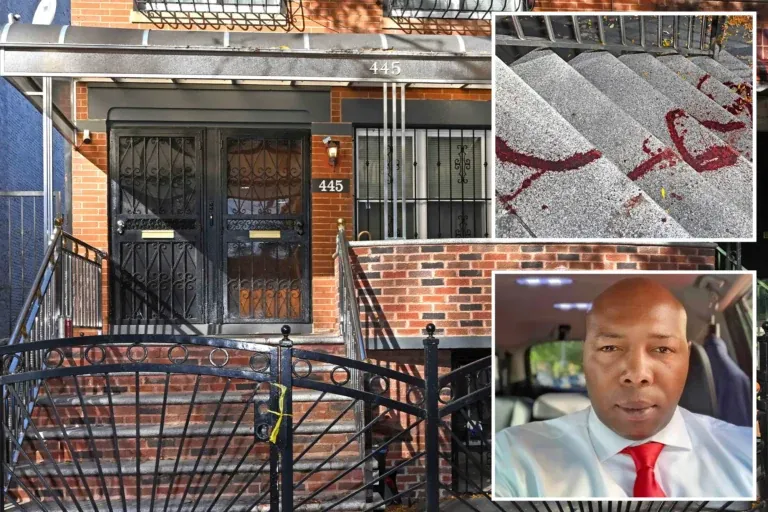

Every morning for the past few weeks, hundreds of individuals, mostly men, have been lining up outside an East Village “reticketing center.” The line stretches around the block, and people patiently wait in the freezing pre-dawn hours, showcasing the new reality of the situation.

The former St. Brigid’s Catholic School on East 7th Street now serves as the main hub for adult migrants who have exceeded their time in shelters. The city has implemented a new policy, which puts a time limit on their stay, prompting these individuals to seek a bed for an additional 30 days.

When individuals are in need of a place to rest, they are provided with a wristband that has a number and a date written on it with a marker. This number indicates the position in line for a cot. The demand for cots is high, with thousands of people waiting across various emergency shelters in the city. Unfortunately, it now takes over a week to secure a cot.

Over the past two weeks, numerous migrants have shared with THE CITY their experiences of waiting for more than seven days to secure a shelter cot. Unfortunately, many are left with no choice but to spend their nights on the streets or in trains. Alternatively, they are directed to an overcrowded waiting room in The Bronx, close to Crotona Park. This waiting room is managed by the city’s Office of Emergency Management.

As the week progressed and the number of individuals waiting for beds increased, the city responded by opening extra satellite waiting rooms. However, in these satellite waiting rooms, migrants are sometimes not permitted to lie down on the floor and face limited access to food. Additionally, they do not have access to bathing facilities. These challenging conditions coincide with freezing temperatures, further exacerbating the hardships faced by these individuals.

“Why is the government allowing us to sleep in the streets? It’s really miserable with this cold,” expressed Bryan Arriaga, a 19-year-old from Mexico. He shared his experience of being turned away from a crowded shelter intake office on December 7th.

After that, he found himself spending a night on the floor of a waiting room in The Bronx and a few more nights sleeping in a public restroom in Jamaica, Queens.

On December 12, he found himself back in the East Village, joining hundreds of others who were facing a similar predicament. Sitting on a park bench, he observed the crowds gathered around the intake site, contemplating his next course of action.

“I just need a place to sleep, a place to bathe, and a comfortable spot to lie down for a good eight hours,” he expressed. “I’m feeling really overwhelmed and down.”

The city’s right to shelter protections have collapsed, impacting adult migrants. They are now given only 30 days in a shelter before they must find a new placement and face the long line at the intake center. Although Adams has repeatedly stated that the aim is to prevent families with children from sleeping on the streets, there will be new restrictions for thousands of migrant families with children as well, as they make up the majority of migrants in shelters.

In the weeks following Christmas, a significant number of 60-day eviction notices were set to expire. This was part of the city’s comprehensive strategy to discourage further migration to New York and to motivate individuals residing in shelters to find alternative housing options.

City Hall did not respond to a request for comment regarding the effective termination of the city’s right to shelter and the situation faced by numerous migrants eagerly awaiting shelter.

‘You’re Killing Us’

At the East Village reticketing site, individuals who manage to enter are provided with meals consisting of sandwiches and fruit. However, each night at 7 p.m., when the facility closes, hundreds of people are turned away and directed to various waiting rooms across the city. These rooms have chairs, but no cots available for them.

Migrants have been consistently directed to the primary overnight waiting room located in The Bronx, which is an hour-and-a-half commute away from the East Village site. According to migrants who have experienced it firsthand, the waiting room has become more cramped, smelly, and dirty over time, and there is no provision for a shower on-site. Moreover, the only food available for sustenance in this setting is limited to crackers and tuna.

A group of migrants has chosen to forgo the nightly journey to The Bronx altogether. For the past two weeks, they have been setting up camp outside the East Village location. The size of the group varies, with fewer than a dozen individuals braving the cold temperatures, while warmer nights can see the group swell to as many as four dozen.

One evening last week, a group of people gathered together to construct fortified shelters using cardboard boxes, salvaged plastic tarps, and wooden slats from discarded bed-frames. As they worked, they exchanged tips on how to endure the cold weather. Some mentioned that they had too much luggage to transport to a different location in the city, while others expressed a preference for sleeping on the sidewalk rather than the overcrowded waiting rooms.

Yaleiza Goyo, a 55-year-old woman from Venezuela, revealed that she has been enduring the harsh conditions of sleeping on the sidewalk outside the reticketing center for four out of the past five nights. In an attempt to stay warm, she has resorted to wearing two pairs of gloves, three pairs of pants, and four jackets. Determined to secure her spot, Yaleiza expressed her resolve, stating, “I have to fight it out, because what else am I going to do?”

On Sunday night, a heavy rainfall forced city workers to relocate those who were sleeping outside to a NYPD gym in Gramercy Park. However, to their dismay, Goyo revealed that they were not allowed to lie down on the floor and were instead forced to spend the entire night sitting up in uncomfortable folding chairs.

“You’re really taking a toll on us. It’s hard to believe you can sleep in such uncomfortable positions. Despite the rain, we had no choice but to stay,” she expressed. With a hint of amusement, she added while completing the final touches on her makeshift cardboard shelter, “Sometimes you just have to find humor in life to keep from breaking down in tears.”

Goyo was part of a growing community of women who were choosing to camp outdoors. Nailett Aponte, a 38-year-old Venezuelan migrant, shared that she had spent the past week waiting for a cot and had been sleeping outside most nights.

In Spanish, she expressed her frustration, stating that there were no beds available for couples or single women. The lack of options was evident, leaving her with no suitable accommodations.

According to Aponte, she finally received a cot assignment on Wednesday, after waiting for seven days.

Migrants interviewed by THE CITY expressed that they had been laid off from their jobs in the restaurant and construction industries while waiting for their turn. They had even missed previously scheduled appointments, which were arranged weeks in advance, in order to obtain their NYC ID cards, a crucial form of identification. They were concerned that they might not receive the necessary paperwork, which would be mailed by the federal government to their previous shelters, allowing them to legally work in the United States.

Trying to secure another cot had likely set them back weeks in their effort to support themselves and move out of shelters permanently.

“I should be working instead of smoking cigarettes and drinking coffee out here,” lamented Krist Benitez in Spanish. He explained that he had been unable to work as a dishwasher as he had spent the past few days sleeping outside, hoping to secure a spot in a shelter. Holding onto a folder of important documents, he expressed his concern about his city ID and Occupational Safety and Health Administration certification, both of which were due to be delivered to his previous shelter. Uncertain about the possibility of retrieving them, Krist feared the impact it would have on his ability to find employment, particularly in the construction industry.”

“I just can’t grasp it,” he expressed his confusion.

Many individuals have already abandoned the idea of waiting. Some fortunate ones have managed to find a room to rent or a couch to crash on. Others have taken advantage of free tickets to other cities and states, exploring new lives outside the city. Unfortunately, numerous people have resorted to unstable living conditions on the streets and subways. Although city officials claim that only 20 percent of those evicted from shelters return for another placement, there is no available data on the whereabouts of the remaining individuals.

After his 30 days in shelters expired, one Venezuelan migrant named David decided to forgo seeking another placement due to the rumors he heard about the disorganized reticketing center.

He has been sleeping in a friend’s van for the past few days.

“It’s tough,” he said to THE CITY in Spanish. “I’ll remain here until I can locate a room.”

‘New Yorkers Are Pissed’

Over the past year, more than 140,000 migrants have made their way to New York City, drawn by the city’s right to shelter. This right has allowed them to have a roof over their heads while they worked towards getting back on their feet. However, the recent chaos we have witnessed in the last two weeks is a culmination of this influx of migrants.

Mayor Adams has been advocating for the elimination of the city’s “right to shelter” policy, asserting that it is outdated and financially burdensome for New Yorkers due to the influx of new residents.

In 1981, when the legal consent decree was established, it only covered adult men and required the city to provide a mere 125 beds for homeless individuals. However, the situation has drastically changed over time. Currently, there are over 122,100 people residing in shelters, including 65,000 migrants. This population is larger than that of Hartford, Connecticut.

During a press conference in October, Adams stated it straightforwardly:

In the city, there are two contrasting viewpoints prevailing at the moment. One viewpoint suggests that anyone from any part of the world can come to New York, and it is the responsibility of the taxpayers, with their limited resources, to provide for them indefinitely. This includes providing food, shelter, clothing, laundry services, as well as medical and psychological care. All of this would be funded by the taxpayers of New York City. On the other hand, there is another viewpoint that stands in opposition to this notion.

Over the years, various mayors, such as Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg, have attempted to lessen the impact of the 1981 Callahan decree, but their efforts proved unsuccessful. It was in 2009 when the city faced a significant challenge as shelter waiting rooms became overcrowded, forcing men and women to sleep on the floors. In response, the Legal Aid Society and the Coalition for the Homeless took the city to court, and a judge compelled the city to open hundreds more beds to accommodate homeless New Yorkers.

Over the past year, thousands of migrants have made their way to New York, repeatedly violating the rules stated in the decree. The decree, which includes guidelines such as maintaining a three-feet spacing between beds, has been disregarded for several months now. During the summer, the protections completely collapsed, leaving hundreds of migrants sleeping on the sidewalk for an entire week during a heat wave.

Adams has been hinting at an upcoming phase for months, in which the city will pinpoint expansive outdoor areas to accommodate migrants. These designated spaces will provide individual tents for each migrant, as well as access to bathrooms and showers. This initiative is a response to the lack of substantial federal funds and immigration policies.

The next phase has arrived, although it doesn’t align with what the mayor had hinted at. It began with the opening of the East Village “reticketing sight” by the Adams administration in October. For the first time, the city explicitly informed migrants that they were not assured a cot, but they did have the option of receiving a plane ticket to any state or country. As a result, numerous cots became available in shelters, allowing those in need to secure another 30-day stay within a reasonable timeframe.

Over the Thanksgiving holiday, the city experienced a sudden influx of migrant adults from the southern border, disrupting the previously stable situation. As a result, the city has been facing a daily shortage of cots for adult migrants.

Diane Enobabor, the founder of the Black and Arab Migrant Solidarity Alliance, refers to it as “organized abandonment.” During this time, there will be those who choose to wait it out, some who will decide to leave, and countless others who will unfortunately slip through the cracks.

Enobabor stated that there would be casualties, and he emphasized the need to acknowledge this reality without reservation. He reiterated the fact that there would inevitably be loss of life.

Attorney Joshua Goldfein, who represents the Coalition for the Homeless through the Legal Aid Society, emphasizes that even though it may presently be challenging to obtain a cot promptly, this does not imply that New Yorkers are no longer entitled to one. Goldfein maintains constant communication with city officials, applying pressure on them to uphold the regulations.

“There is an existing court order that is still in effect,” he stated. “It is evident that they are not complying with it. Therefore, the real issue at hand is determining the appropriate remedy for this situation.”

‘I Don’t Have Deportation Powers’

Despite facing criticism from the progressive left, Adams remains in line with the majority of New Yorkers, who are growing increasingly dissatisfied with the current situation. The mayor attributes the need for unexpected mid-year budget cuts, which would impact essential services such as police, fire, sanitation, schools, and libraries, to the high cost of migrant care.

The city has spent billions on the crisis, but the federal government has only offered to reimburse $159 million. However, the federal immigration policies, which allow people to seek asylum but prevent them from working legally for months, create a challenging situation.

During a press briefing on Tuesday, Adams expressed his response to the poll numbers, stating that the individuals he interacts with are “pissed off” and he empathizes with their anger.

“People often question me, Eric, about why I am allowing the buses to come in and why I am not stopping them,” he shared. In response, he stated, “I want to clarify that I do not possess the authority to deport individuals or redirect buses. My role is focused on budget management and maintaining fiscal stability.”

‘No One Told Me the Truth’

Jesus Lopez, an 18-year-old from Venezuela, crossed the border alone approximately a month ago. After his arrival, he managed to secure a free bus ride from Texas to Chicago. In Chicago, he spent three weeks sleeping on the floor of a police precinct. However, upon hearing from fellow migrants that New York would offer better opportunities, he decided to make his way there. Unfortunately, upon arrival in New York by bus, he found himself lost and spent about a week wandering the streets without a jacket. He resorted to sleeping on the subways and any warm spot he could find.

During his train journey, someone informed him about the primary center for migrants at Roosevelt Hotel in Midtown.

Lopez shared that despite city officials prioritizing placements for newly arrived adults in New York, he was turned away and told to go to the reticketing site. Along with thousands of others, he sought a 30-day stay there. Lopez described spending the past week going back and forth between the East Village waiting room during the day and the waiting room in The Bronx at night. His sleep and meals were disrupted, and he didn’t have the opportunity to shower.

The freezing cold temperatures on Tuesday night made his teeth chatter as he stepped outside the overcrowded overnight waiting room in The Bronx. Lopez mentioned that his time in New York had been relatively better than his previous experience in Chicago, but the situation was still quite unsettling for him.

“I can’t believe no one informed me about this. It’s shocking,” he exclaimed in Spanish, expressing his surprise at being assigned the number 3,752 for a cot. “I’m at a loss for words. I don’t know how to process this.”