Alabama Slave Owner’s Descendants Attempt to Make Amends

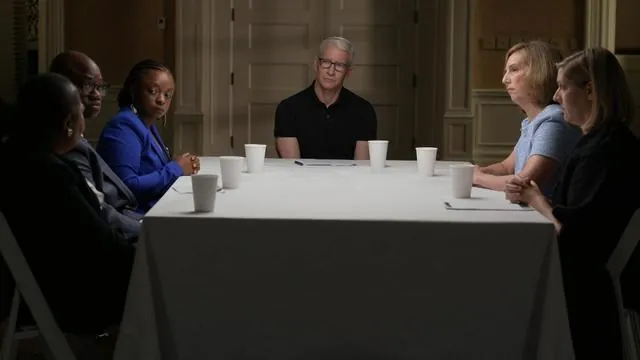

During the summer, a significant meeting took place between the descendants of enslaved Africans and the descendants of the slave owner who financed their journey to America. This meeting was a result of years of persistent effort to arrange reconciliation talks between the two groups.

For years, the descendants of Timothy Meaher, a slave owner in Alabama who hired Capt. William Foster to smuggle 110 Africans to Mobile on his ship, Clotilda, had refused to meet with the descendants of those who were brought to the U.S. as slaves.

The Meaher family business underwent a shift in leadership last year, with the younger generation taking charge. In the past year, they have been actively seeking ways to make reparations for their family’s past actions.

What was the Clotilda?

In 1860, slavery was still permissible in the southern region of the United States. However, importing enslaved individuals into America had been banned since 1808. Timothy Meaher, during this time, hired Captain Foster to lead a ship. Meaher sent the ship to the Kingdom of Dahomey, located in West Africa, where Foster’s journal entries indicate that he bought the captives by paying “$9,000 in gold.”

The Clotilda holds the distinction of being the final documented ship to transport enslaved Africans to America.

What happened to the enslaved Africans?

After enduring five years of enslavement, the Clotilda survivors were finally granted their freedom. One of the survivors, Kossula, was known by the name Cudjo Lewis to his enslaver. In an interview conducted in 1914, Kossula revealed that they requested Timothy Meaher to assist them in returning to Africa, but he refused. Additionally, Meaher tried to impede their voting rights. Despite these challenges, some of the survivors managed to secure employment in a sawmill that Meaher owned.

Back in 1868, just three years following the abolition of slavery, a group of 30 Africans who were freed from the Clotilda ship founded Africatown. This remarkable community stands as the sole surviving African-founded community in the United States today, with some of their descendants still residing there to this day.

Africatown today

Africatown’s population has significantly decreased to only 800 individuals, from a booming 12,000 during the 1960s. Unfortunately, the construction of an interstate highway in the early 1990s divided the community, and the few remaining homes now stand amidst factories and chemical plants.

Tax records reveal that Timothy Meaher’s descendants are still in possession of approximately 14% of the land in Africatown, a historic area. The Meaher name can be seen on property markers and street signs in the vicinity. According to court documents, their real estate and timber ventures are valued at around $36 million.

In 2018, experts discovered the remains of the Clotilda in a nearby area of the Mobile River. After conducting further investigations, maritime archaeologists were able to confirm that the wreckage was indeed that of the Clotilda in the following year.

A total of $10 million from various sources, including city, state, federal, and philanthropic funds, has been invested in the revitalization of Africatown since the discovery of Clotilda.

Despite the discovery of the Clotilda, the descendants of Meaher have been reluctant to meet with the descendants of the enslaved Africans who were brought on the ship. In 2020, 60 Minutes reached out to four members of the Meaher family for an interview, but all either declined or did not respond to the request.

A historic change

In July, descendants of the Clotilda slaves gathered at Mobile’s history museum. One of the attendees was Pat Frazier, the great-great-granddaughter of Lottie Dennison, who was representing the Clotilda Descendants Association alongside Joycelyn Davis and organization President Jeremy Ellis.

Frazier expressed her disbelief, “I never thought this day would come, ladies. People kept saying that the Meahers have been silent, and every attempt to approach them had been through their lawyers.”

Meg Meaher and her sister Helen, who are the great great granddaughters of Timothy Meaher, sat facing the Clotilda descendants.

Meg Meaher expressed her happiness on finally breaking the silence and narrowing the distance. “We were silent for a prolonged period and distant for an extended time. It’s a relief to finally break the silence,” she said.

Helen Meaher spoke out about her family’s prolonged silence on the matter.

“Our family is similar to many others, with layers, complexities, and some dysfunctions. We even found ourselves in a lawsuit among family members, which was finally resolved just a year ago. Now, it’s up to our generation to step up and move forward,” she explained.

Last year, Helen Meaher, who grew up just a few miles away from Africatown, visited the place for the first time while volunteering at a food bank. In 2021, she and Meg sold a plot of land in Africatown to the City of Mobile for $50,000, which is only a fraction of its appraised value. This land will serve as the new home for community development organizations and a food bank.

In 10 years, her aspiration for Africatown is to see it flourishing as a vibrant community.

According to Frazier, the Meaher sisters cannot be held accountable for the actions of their ancestor.

She expressed her desire for them to acknowledge the advantages they gained from their behavior and the disadvantages it brought upon her community. “While they have inherited wealth for multiple generations, the original slaves and their offspring haven’t been as fortunate,” she explained.

Reconciliation, not reparations

During the meeting, the Clotilda descendants emphasized their desire for reconciliation rather than reparations.

Ellis expressed her belief in providing her daughter with the same quality of education that the Meaher family had. She emphasized that this level of education should be offered to all descendants, not just a select few.

According to their beliefs, ownership of certain parcels of land in Africatown’s historical district should rightfully belong to them.

Upon assuming her new role in her family, Helen Meaher expressed uncertainty about whether her family is profiting from any parcels of land in Africatown. She acknowledged the need to review this matter before making any definitive statements.

She expressed that they are still remaining open-minded and are currently working on determining the next steps. She also emphasized that she is not closing any doors on any possibilities.

The meeting between the descendants lasted for a total of two hours. While no financial commitments were made, the Meahers have already started removing their property markers. They mentioned that they are in consultation with financial planners and local groups to determine their next course of action.

According to Ellis, the individuals involved have shown a willingness to make things right. They are actively seeking to approach the situation with care and consideration. “I can appreciate where they’re coming from and their desire to be deliberate in their decision-making,” Ellis remarked.

The descendants of Clotilda express their hope that their gathering can serve as a blueprint for similar discussions throughout the country.

Ellis expressed her hope that the nation can use this as a model for reconciliation and that it will initiate the healing process for numerous descendants. She stated, “My aim is to showcase the true meaning of reconciliation and provide a path for those who seek it.”

How many of the slave descendants have thought about how fortunate they are to be in the U.S. and not in Africa?